Cargolifter – a failed piece of air travel history

- Posted by Gerhard Pramhas

- On 20. December 2017

Do you remember the German company Cargolifter? By no later than 1998 the company that was planning to build a gigantic airship for transporting payloads of up to 160 tons was a widespread topic of conversation. Despite the fact that the innovative concept was an ingenious one, and although there was a clear case for the notion being a very relevant one, the company failed in 2002. Why? That is what I would like to explain to you today.

Idea, need and early company successes

According to a study by Germany’s Verband Deutscher Maschinen- und Anlagenbau e.V. (VDMA), the global market volume for heavy goods transport in 1995 stood at about 30 million tons. To this day, that market volume is broadly divided across three forms of freight transport: land, sea and air. Each sector has its preferred areas of application:

-

Sea freight

- Of particular interest to goods where time in transit is not a primary consideration

- Often the only transport option

- The least expensive and the most flexible solution

-

Air freight

- Guarantees fast transport

- Much more expensive than transport by sea

- Helicopters can provide direct transport into places where aircraft cannot operate (the biggest transport helicopter can carry a max. payload of 20 tons)

- Payloads weighing more than 20 tons are transported by aircraft

-

Road transport

- Ultra-heavy transport operations require elaborate planning and are often very costly

- Average road speed for transport operations of this kind: 8 km/h

- Often unavoidable, depending on location

- Often, machines need to be designed with transport requirements in mind, to ensure that they can be loaded onto a road transporter or into a container

As you can see, none of these options are perfect, and depending on the dispatch and delivery location, the transport of freight can often involve interdisciplinary teamwork.

It was because of this that the VDMA saw great potential in the Cargolifter airship, that was to be capable of transporting payloads of up to 160 tons. The Cargolifter was also intended to be flexible in terms of the volume of freight, which could simply be picked up on the factory premises and transported straight to its intended destination. In terms of range, the airship would achieve much greater distances than a helicopter. The VDMA forecast that the company would be tapping into a market potential of three million tons, or ten percent of the entire world market. 1

A wide array of shareholders also identified this great potential. When the company was founded in 1996, it already had 90 shareholders on board as founding members. Just one year later, that figure had risen to more than 600 shareholders. And just one year after that, early in 1998, the number of private and institutional shareholders had risen to 1350. Also in 1998, on a former Soviet military airbase in the Brand region of Brandenburg, construction work began on the construction hangar, which remains to this day the largest free-standing structure of its kind in the world. In 2000, the company was floated on the stock exchange, and everything appeared to be going to plan.

Gigantic fall after flying high

Shares were selling well. More than 70,000 shareholders signed up for this stock. However, in 2001, the first downturn happened: It proved impossible to bring the Airbus Group on board, causing development delays to the airship.

By 2002, share prices tumbled to basement levels. From an original share price of €15.50, by May, each share was only worth €1.02. Later that same year, the company declared itself insolvent and went into liquidation. Although several attempts were made to save the company, this did not prove successful. In 2003, the company began to auction off its equipment. Office furniture, tools, computers and even the construction hangar – now known as the “Tropical Islands” leisure park – were sold off. However, what actually happened here?

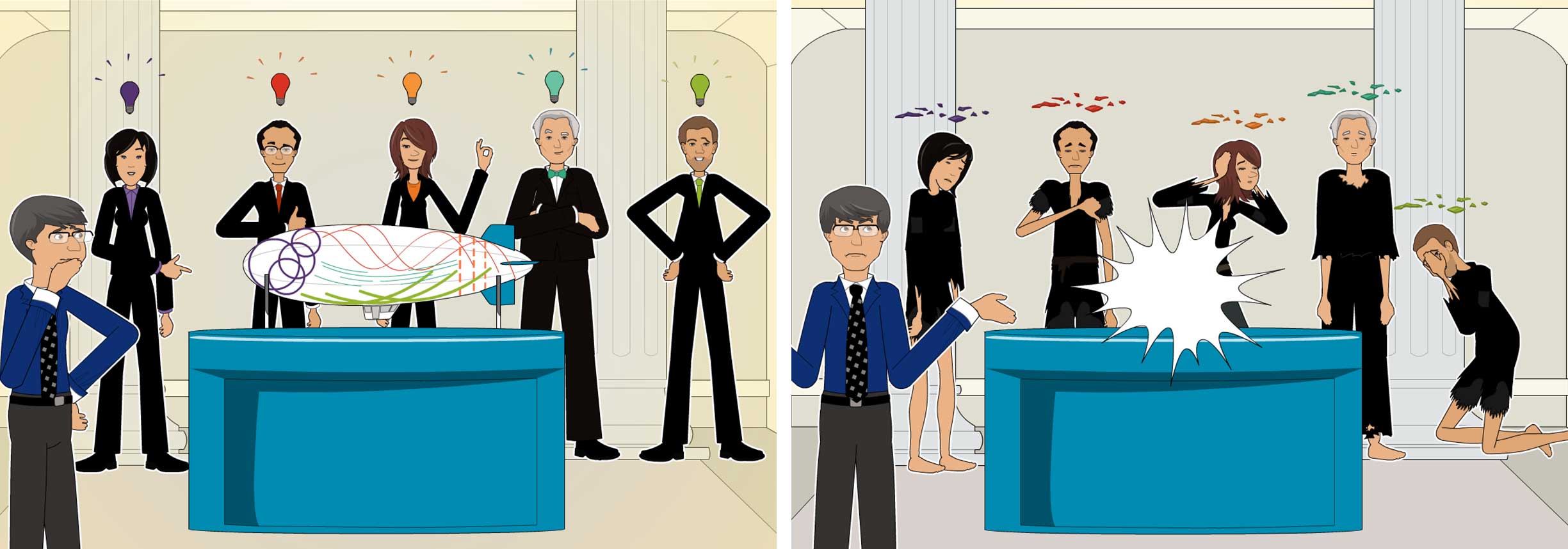

There were many reasons for this failure. Right at the beginning of this development project, questions should have been asked about the technological and financial risk assessment. It failed through the absence of a realistic project schedule, of an appropriate project management team, and also on the level of fixed costs involved.

Other questions that ought to be have been clarified:

- Was it known back in 1996 why airships had never proven successful before this?

- Was the technology genuinely available in a fundamental and tried-and-tested form?

- What did the financial structure look like?

- Were too many people and institutions involved in the dialogue?

- On this technological terra incognita, was the collaboration of an experienced corporation in place?

Tips to prevent your personal crash

You can learn quite a few things from the story of Cargolifter. For example: Make yourself realistic time and financial plans at the start of your product development process. There is no point in being dishonest with yourself and ‘talking up’ the figures.

Before you start to implement a real product, you must test the basic technology very rigorously indeed. You should answer a few simple questions for yourself:

- How realistic is the financial plan being presented?

- How feasible do you believe the presented technology roadmap to be?

If doubts arise, you have three options:

- You embark upon your entrepreneurial risk and you dispense with further safeguards. A perfectly legitimate course of action: there is a certain level of risk in everyday business life that no-one can protect you against.

- To limit the extent of risk, you should commission a study for you and your financial backers.

- To that end, take the opportunity of having a 30-45 minute telephone or Skype conversation with me. Together, we can come up with the ideal way forward in your situation.

Naturally, within that short period of time, I will be unable to provide you with turnkey solutions, but you will get some valuable tips about where your journey might lead you. Well then, take your opportunity and contact me. I look forward to your call on +43 676 956 0164 or to your Skype enquiry (gerhard.pramhas).

By the way: If you would like even more information about the Cargolifter, I can strongly recommend this german only article from manager magazin to you.